Task: Consider whether or not any photographic ‘characteristics’ are important to your own practice. Identify any approaches / practices / practitioners that specifically resonated with you. Summarise your independent research (eg interviews or reviews of relevant practice / reading). Evaluate the development of your own photographic practice to date. Reflect on the peer / tutor feedback received on your current / future practice. What are your action points? Where are you going next?

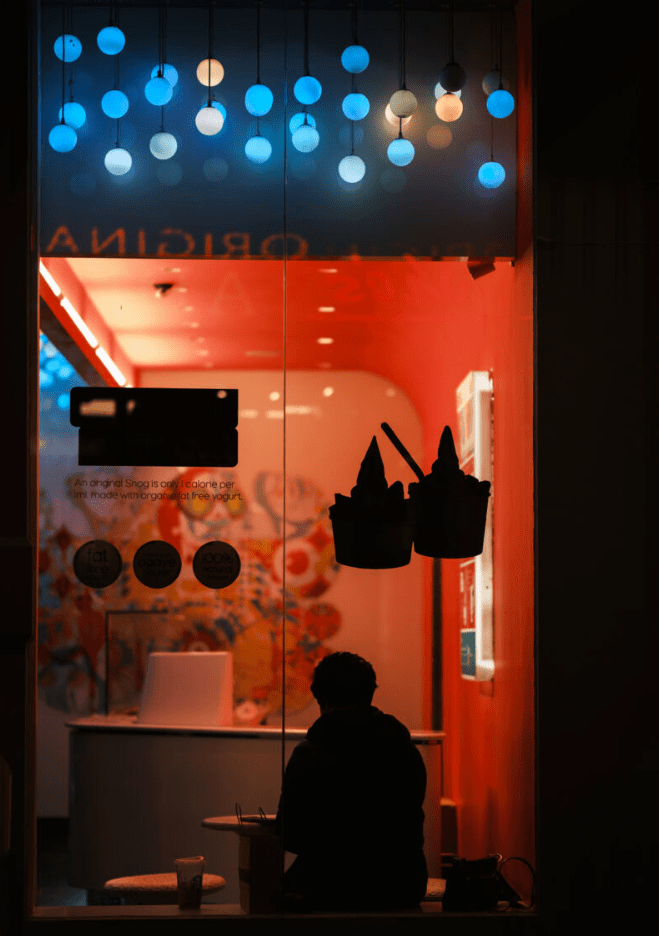

The ability of the still image to connote rather than denote is not necessarily unique to the photographic image, but nonetheless remains an important driver for my love of the craft. The ability to decide consciously the time, format, perspective and frame allows me as the photographer to consciously decide what remains in the frame as a signifier and what is left out. Whilst Stewart Hall points out the differences that can exist between encoding and decoding, one can at least play with the viewer’s emotions sometimes predictably other times not.

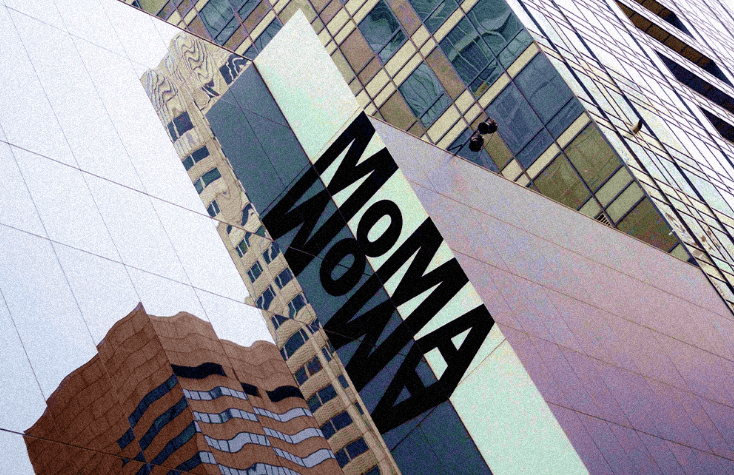

Unexpectedly, the impact of the first week’s study has been significant on my beliefs, ambitions, and future direction for my practice. The challenge of creating, consuming, and critiquing images with regards to them being a picture of vs a picture about something is now firmly established in my consciousness. I am looking to create a body of work about rather than of something. Furthermore, I now recognise , thanks to Hall’s coding decoding theory (Hall 2014) my naivety in always seeking to control the narrative for my images, recognising also how limiting this might be as a creative exercise.

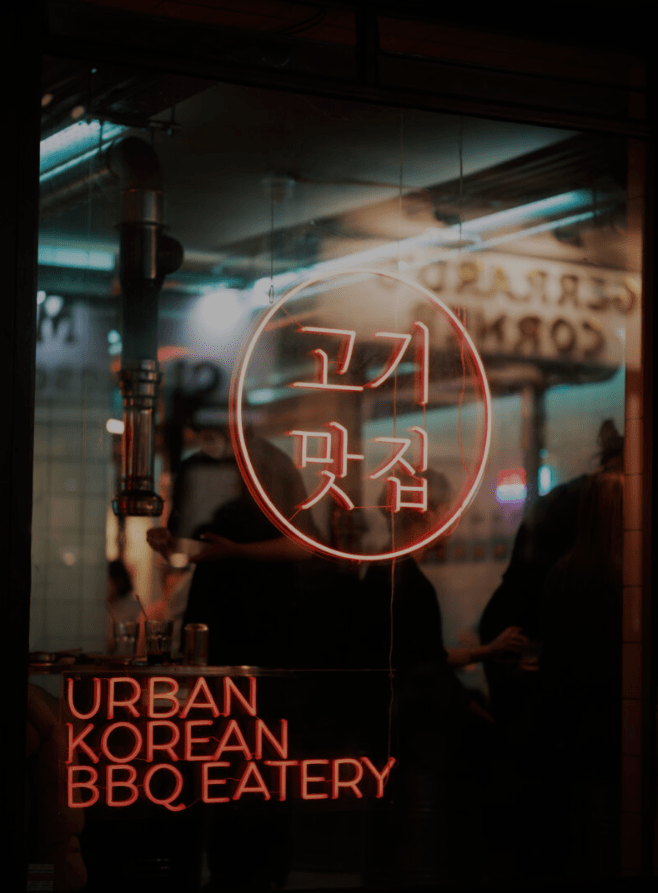

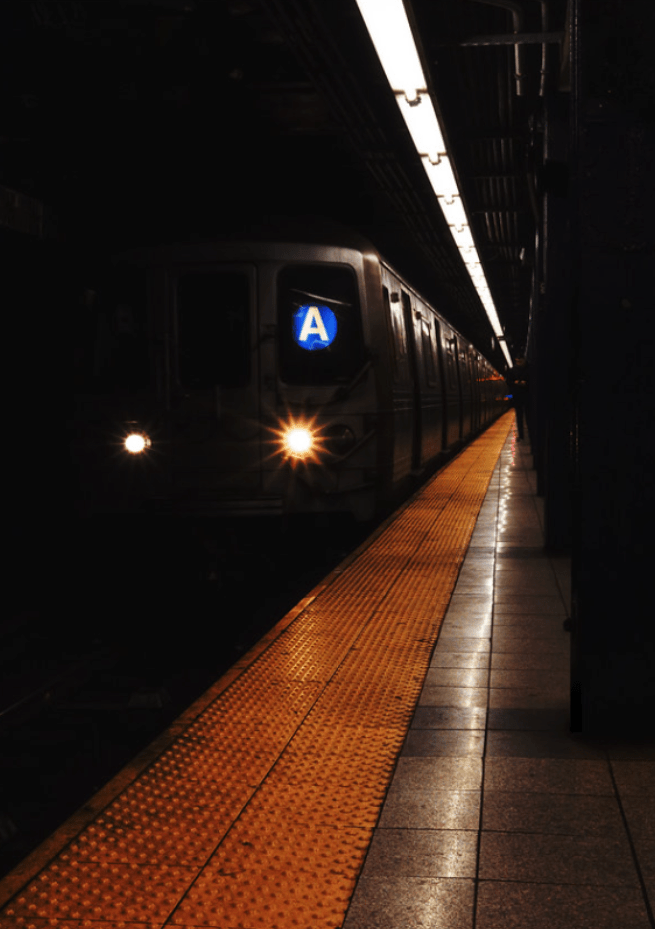

In shifting topics, I must now explore the context in which it will sit. I will need to research photographers who have created evocative cinematic images that evoke feelings of uneasiness, isolation, depression, anxiety, and loneliness. My initial research highlighted Todd Hido and Robert Darch, both of whom create images that invite the viewer to place themselves inside the image and experience a sense of disorientation and uneasiness. I will look to explore their work and practices while looking for other photographers as contextual material.

My first 1:1 tutor meeting with Paul was highly instructive. Although I thought I had been smart in creating a series of comprehensive frameworks and objectives, Paul explained that I could not control the scopic regimens (how the narrative was decoded). I should loosen my desire for control, allowing the work to speak for itself. Other helpful suggestions included the book Photography Cinema and Memory and the film Emys Men.

My next objective, is to scope out the photographic work that I will need to create for my work-in-practice assignment. This will be both a study of my potential subject matter as well as the processes I will experiment with to achieve the required visual effects. At the same time, I will need to begin the journey of evaluating what is required for the second part of the assignment, my Critical Review of Practice. Time perhaps to create an in-depth and informed to-do list and deadline tracker.

LIST OF FIGURES

Todd Hido’. 2024. Toddhido.com [online]. Available at: http://www.toddhido.com/homes [accessed 24 Jan 2024].

REFERENCES

Hall, S., 2014. Encoding and decoding the message. The discourse studies reader: Main currents in theory and analysis, pp.111-121.